Models#

Music retrieval systems have evolved from simple classification approaches to more sophisticated methods that can handle natural language queries. Audio-text joint embedding represents a significant advancement in this field, offering a powerful framework for matching music with textual descriptions. This approach, built on multimodal deep metric learning, enables users to search for music using flexible natural language descriptions rather than being constrained to predefined categories. By projecting both audio content and textual descriptions into a shared embedding space, the system can efficiently compute similarities between music and text, making it possible to retrieve music that best matches arbitrary text queries.

Multi-modal Joint Embedding Model Architecture#

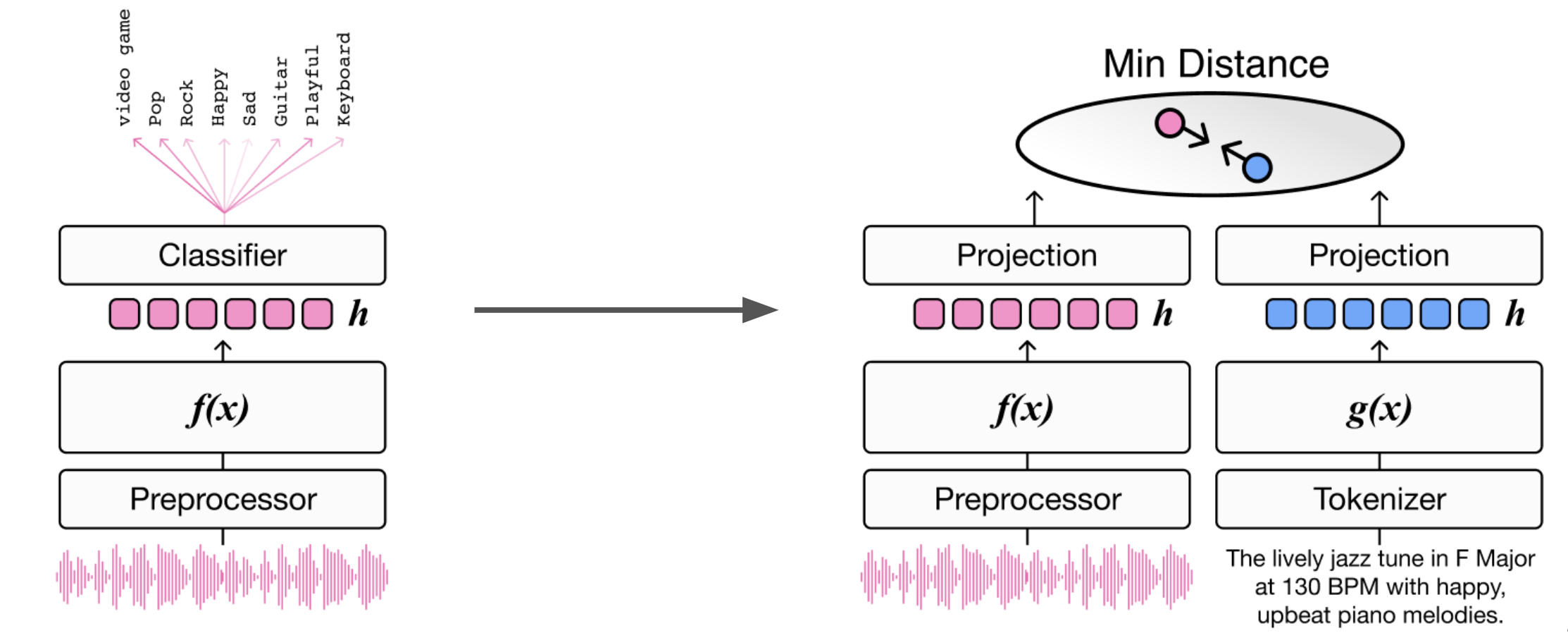

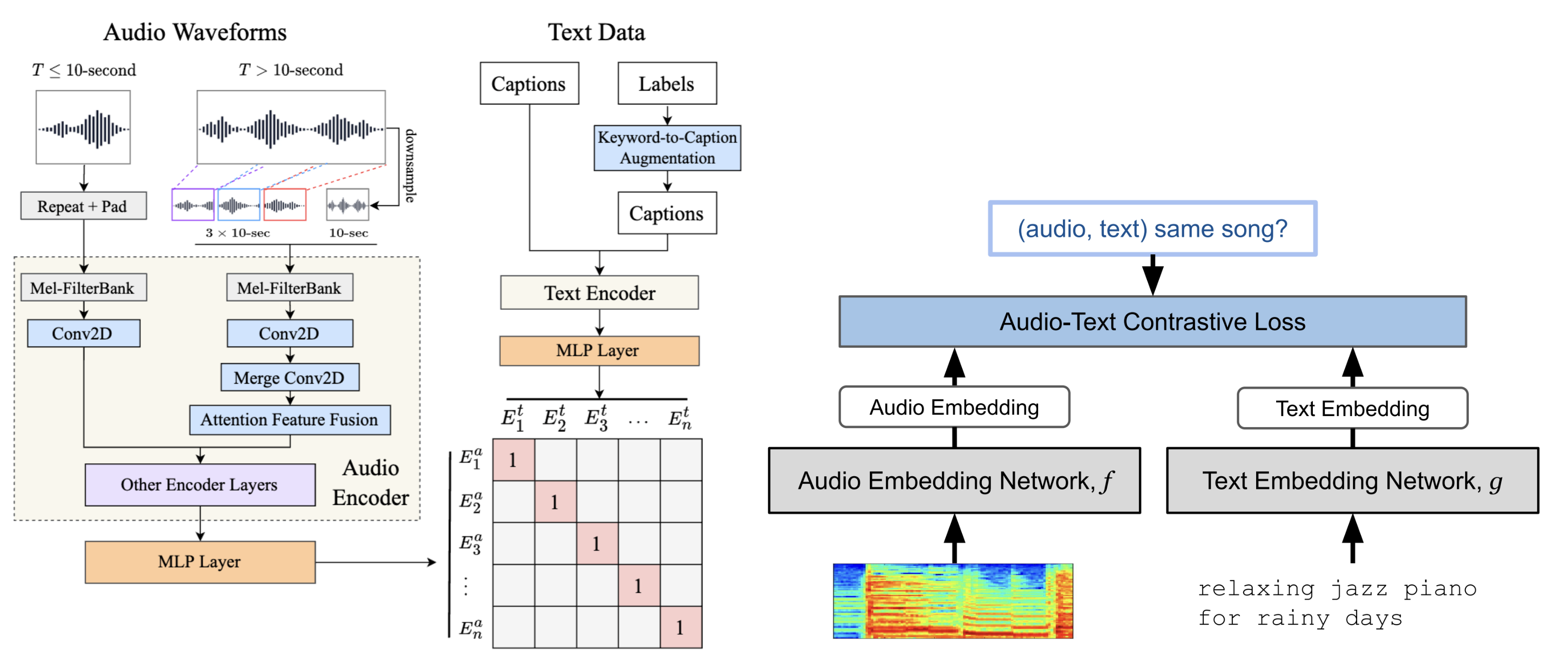

At a high level, a joint embedding model is trained using paired text and music audio samples. The model learns to map semantically related pairs close together in a shared embedding space while simultaneously pushing unrelated samples further apart. This creates a meaningful geometric arrangement where the distance between embeddings reflects their semantic similarity.

Let \(x_{a}\) represent a musical audio sample and \(x_{t}\) denote its paired text description. The functions \(f(\cdot)\) and \(g(\cdot)\) represent the audio and text encoders respectively, which are typically implemented as deep neural networks. The audio encoder processes raw audio waveforms or spectrograms to extract relevant acoustic features, while the text encoder converts textual descriptions into dense vector representations. The output feature embeddings from each encoder are then mapped to a shared co-embedding space through projection layers that align the dimensionality and scale of the embeddings. During training, the model typically employs either triplet loss based on hinge margins or contrastive loss based on cross entropy to learn these mappings. These loss functions encourage the model to minimize the distance between positive pairs while maximizing the distance between negative pairs, effectively shaping the structure of the embedding space.

Metric Learning Loss Functions#

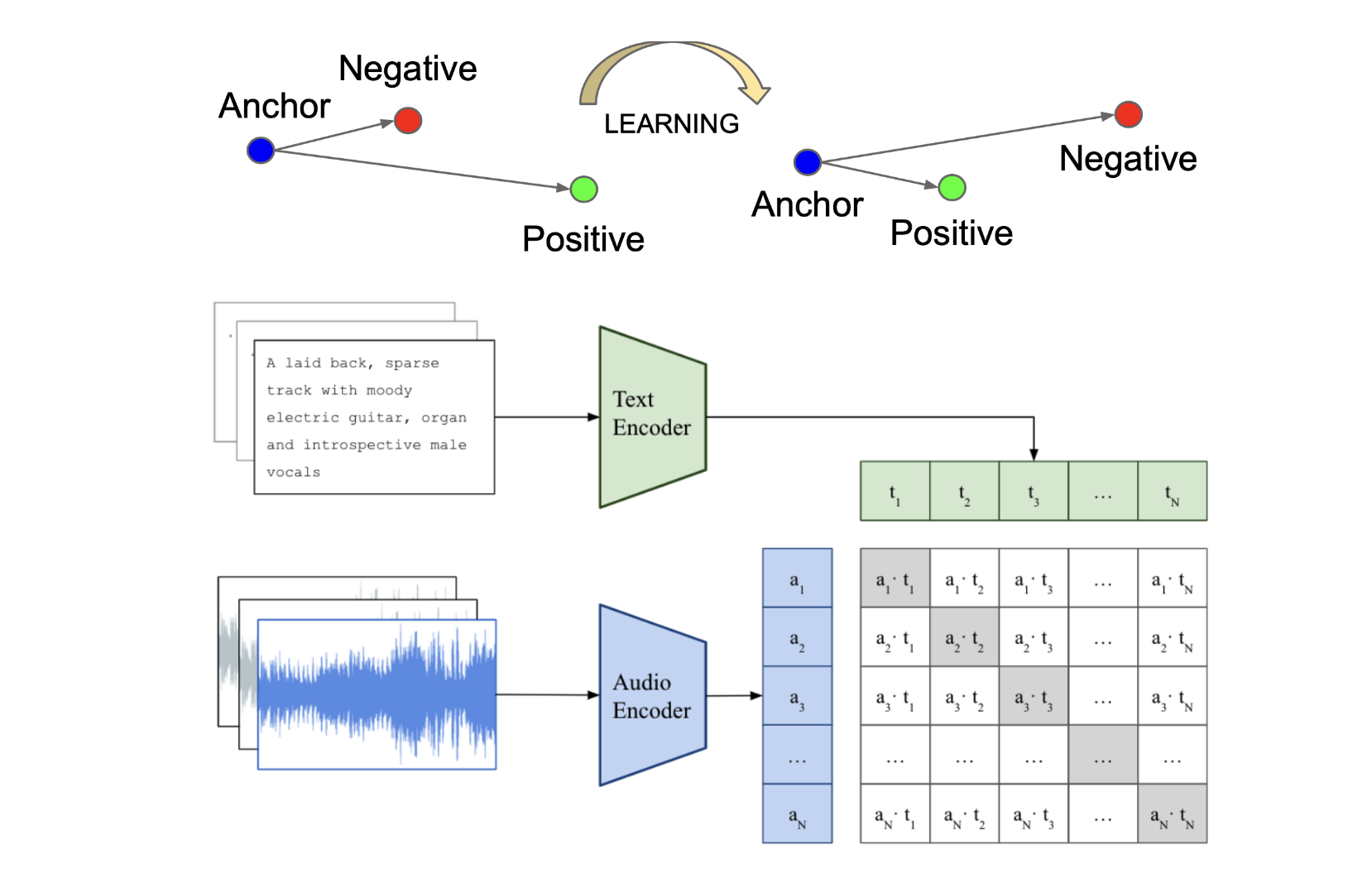

The most common metric learning loss functions used to train joint embedding models are triplet loss and contrastive loss.

The goal of triplet-loss models is to learn an embedding space where semantically relevant input pairs are mapped closer together than irrelevant pairs in the latent space. For each training sample, the model takes an anchor audio input, a positive text description that matches the audio, and a negative text description that is unrelated. The objective function is formulated as follows:

where \(\delta\) is the margin hyperparameter that controls the minimum distance between positive and negative pairs, \(f(x_{a})\) is the audio embedding of the anchor sample, \(g(x_{t}^{+})\) is the text embedding of the positive description, and \(g(x_{t}^{-})\) is the text embedding of the negative description. The dot product measures similarity between the embeddings. The loss function encourages the similarity between the anchor and positive pair to be greater than the similarity between the anchor and negative pair by at least the margin \(\delta\).

The core idea of contrastive-loss models is to reduce the distance between positive sample pairs while increasing the distance between negative sample pairs across an entire mini-batch of samples. Unlike triplet-loss which only uses one negative sample per anchor, contrastive-loss models leverage multiple negative samples that exist within a mini batch of size \(N\). During training, the audio and text encoders are jointly optimized to maximize the similarity between \(N\) positive pairs of (music, text) associations while minimizing the similarity for \(N \times (N-1)\) negative pairs. This approach, known as the multi-modal version of InfoNCE loss [OLV18], [RKH+21], allows for more efficient training by considering many negative examples simultaneously. The loss is formulated as follows:

where \(\tau\) is a learnable parameter.

What is the Benefit of Joint Embedding?#

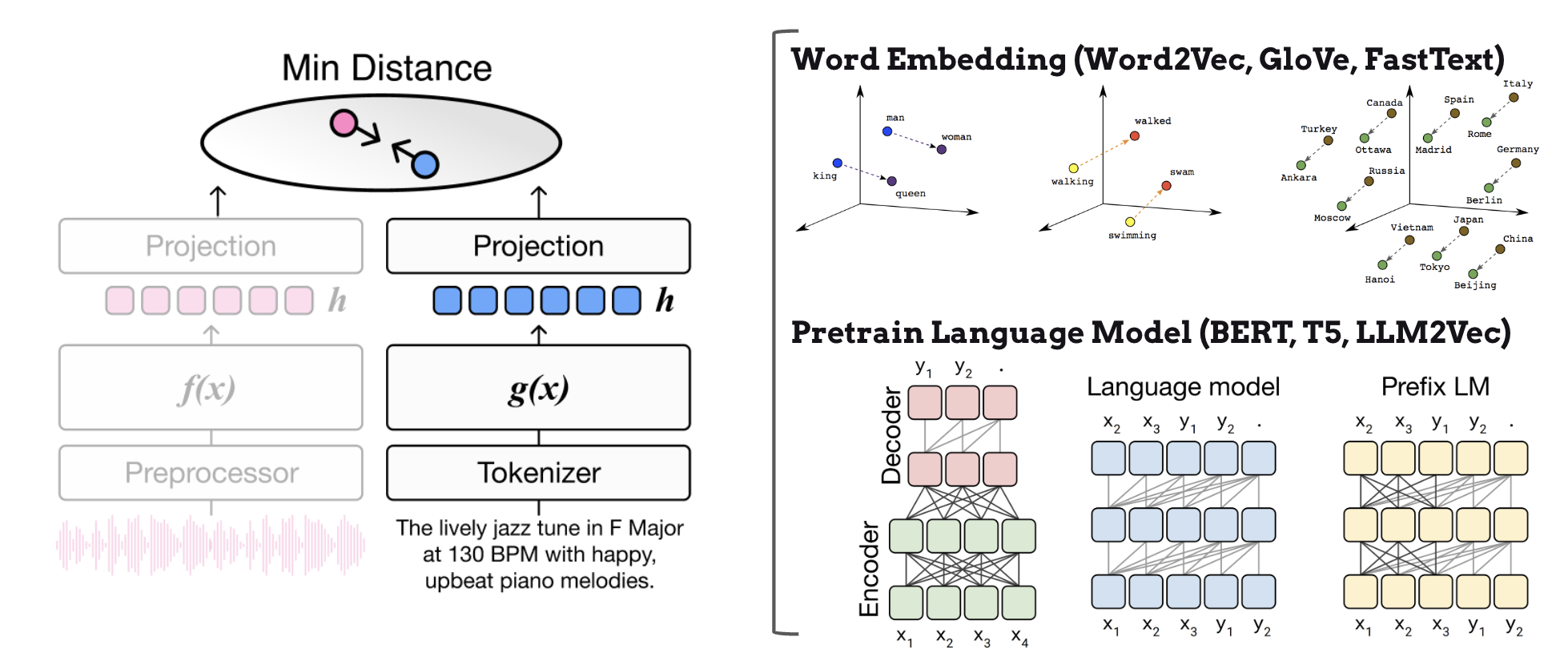

The key advantage of joint embedding is that it allows us to leverage the embedding space of pretrained language models as supervision, rather than being limited to a fixed vocabulary. Pretrained language models, which are trained on vast text corpora from the internet, effectively encode rich semantic relationships between words and phrases. This enables music retrieval systems to handle zero-shot user queries efficiently by utilizing these comprehensive language representations that capture nuanced meanings and associations.

Furthermore, by incorporating language model encoders, we can effectively address the out-of-vocabulary problem through advanced subword tokenization techniques such as byte-pair encoding (BPE) or sentence-piece encoding. These tokenization methods intelligently break down unknown words into smaller subword units that already exist in the model’s vocabulary. For example, if a user queries an unfamiliar artist name “Radiohead”, the tokenizer might break it down into “radio” + “head”, allowing the system to process and understand this novel term based on its constituent parts.

This powerful combination of pretrained language model semantics and subword tokenization provides two crucial benefits:

Flexible handling of open vocabulary queries through language model representations - The system can understand and process a virtually unlimited range of natural language descriptions by leveraging the rich semantic knowledge encoded in pretrained language models

Robust processing of out-of-vocabulary words through subword tokenization - Even completely new or rare terms can be effectively handled by breaking them down into meaningful subword components, ensuring the system remains functional and accurate when encountering novel vocabulary

Models#

In this section, we comprehensively review recent advances in audio-text joint embedding models for music retrieval. We examine how these models have evolved from simple word embedding approaches to more deep architectures leveraging pretrain language models and contrastive learning. Additionally, we discuss practical design choices and implementation tips that can help researchers and practitioners build robust audio-text joint embedding systems.

Audio-Tag Joint Embedding#

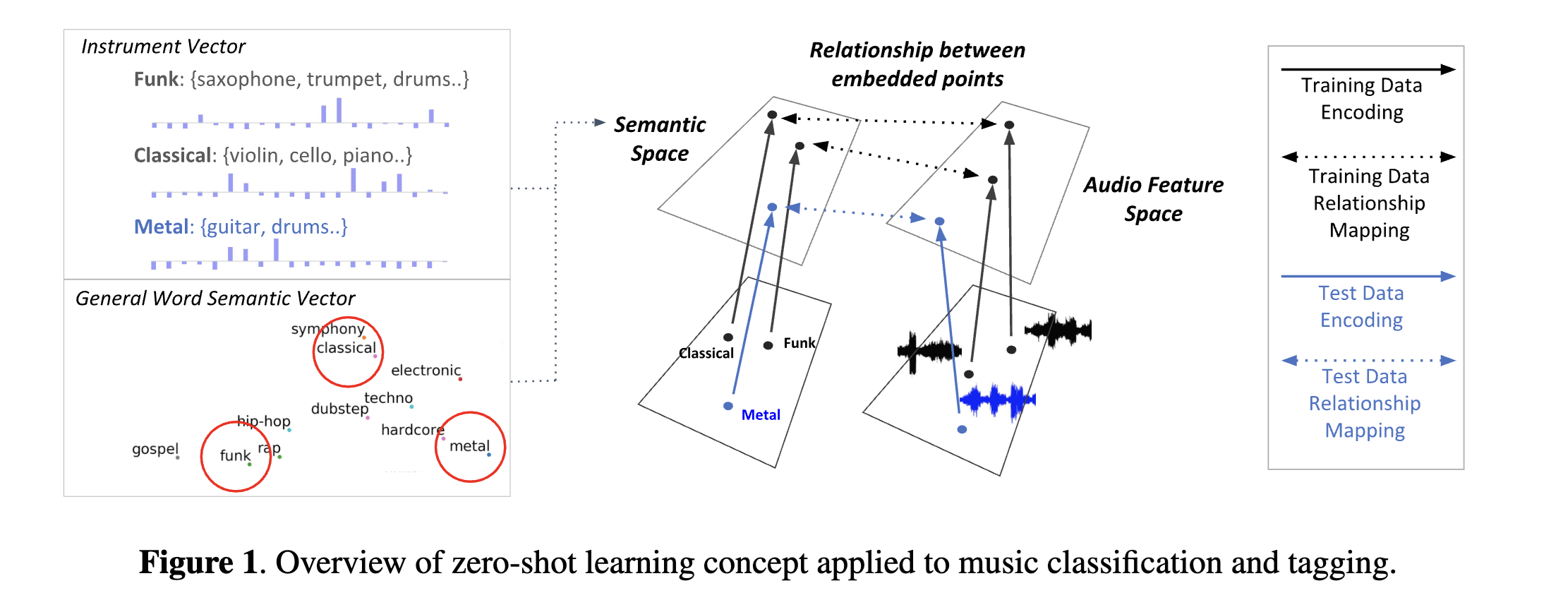

The first significant audio-text joint embedding work introduced to the ISMIR community was presented by [CLPN19]. Their research demonstrated the effectiveness of pretrained word embeddings, specifically GloVe (Global Vectors for Word Representation), in enabling zero-shot music annotation and retrieval scenarios. This approach allowed the model to understand and process musical attributes it had never seen during training.

Building on this foundation, [WON+21] expanded the scope beyond pure audio analysis by incorporating collaborative filtering embeddings. This innovation allowed the model to capture both acoustic properties (how the music sounds) and cultural aspects (how people interact with and perceive the music) simultaneously. Further advancements came from [WON+21] and [DLJN24], who tackled a critical limitation of general word embeddings - their lack of music-specific context. They developed specialized audio-text joint embeddings trained specifically on music domain vocabulary and concepts, leading to more accurate music-related representations.

However, these early models encountered significant limitations when handling more complex queries. Specifically, they struggled with multiple attribute queries (e.g., “happy, energetic, rock”) or complex sentence-level queries (e.g., “a song that reminds me of a sunny day at the beach”). This limitation stemmed from their reliance on static word embeddings, which assign fixed vector representations to words regardless of context. Unlike more advanced language models, these embeddings cannot capture different meanings of words based on surrounding context tokens. Consequently, research utilizing these models was primarily restricted to simple tag-level retrieval scenarios, where queries consisted of single words or simple phrases.

Audio-Sentence Joint Embedding#

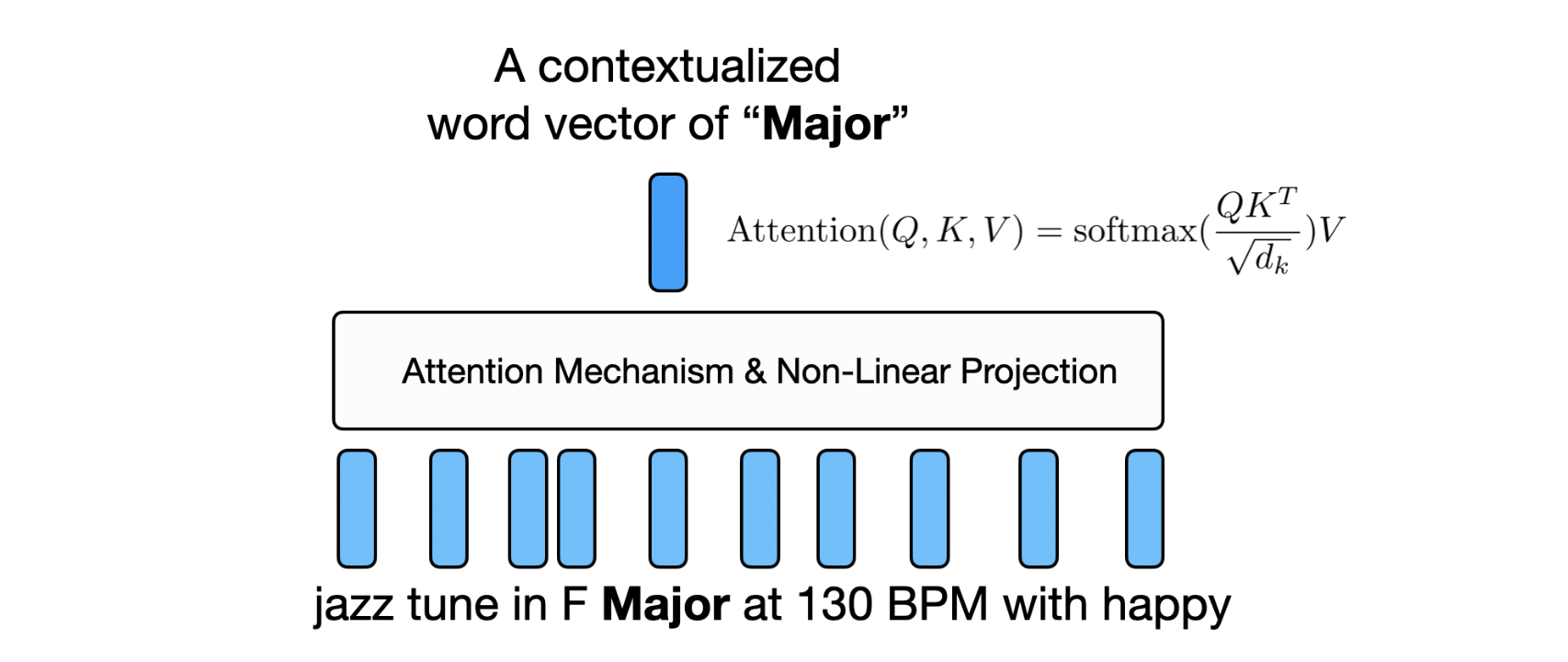

To better handle multiple attribute semantic queries, researchers have shifted their focus from word embeddings to bi-directional transformer encoders [DCLT18] [Liu19]. These transformer models offer several key advantages over static word embeddings:

Contextualized Word Representations: Unlike static word embeddings that assign a fixed vector to each word, transformers generate dynamic representations based on the surrounding context. For example, the word “heavy” would have different representations in “heavy metal music” versus “heavy bass line”.

Attention Mechanism: The self-attention layers in transformers allow the model to weigh the importance of different words in relation to each other. This is particularly useful for understanding how multiple attributes interact - for instance, distinguishing between “soft rock” and “hard rock”.

Bidirectional Context: Unlike autoregressive transformers (e.g., GPT) that use causal masking to only attend to previous tokens, BERT and RoBERTa use bidirectional self-attention without masking. This allows each token to attend to both previous and future tokens in the sequence. For example, when processing “upbeat jazz with smooth saxophone solos”, the word “smooth” can attend to both “upbeat jazz” (previous context) and “saxophone solos” (future context) simultaneously, enabling richer contextual understanding. This bidirectional attention is particularly important for music queries where the meaning of descriptive terms often depends on both preceding and following context.

Recent works have demonstrated the effectiveness of these transformer-based approaches. [CXZ+22] evaluated BERT langauge model emedding with the MagnaTagATune dataset, showing improved accuracy in handling queries with multiple genre and instrument tags. Similarly, [DWCN23] utilized BERT to process complex attribute combinations on the MSD-ECALS dataset, demonstrating better understanding of musical descriptions like “electronic, female vocal elements” or “ambient, piano”.

These studies leveraged existing multilabel tagging datasets to train and evaluate the language models’ ability to understand multiple attribute queries. The results showed that transformer-based models could not only handle individual attributes but also effectively capture the relationships and dependencies between multiple musical characteristics in a query.

To handle flexible natural language queries, researchers focused on noisy audio-text datasets [HJL+22] and human-generated natural language annotations [MBQF22]. Thanks to sufficient dataset scaling and contrastive loss with the advantage of large batch sizes, they built joint embedding models with stronger audio-text associations compared to previous studies. [MBQF22], [HJL+22], [WCZ+23] demonstrated that contrastive learning with large-scale audio-text pairs could effectively learn semantic relationships between music and natural language descriptions.

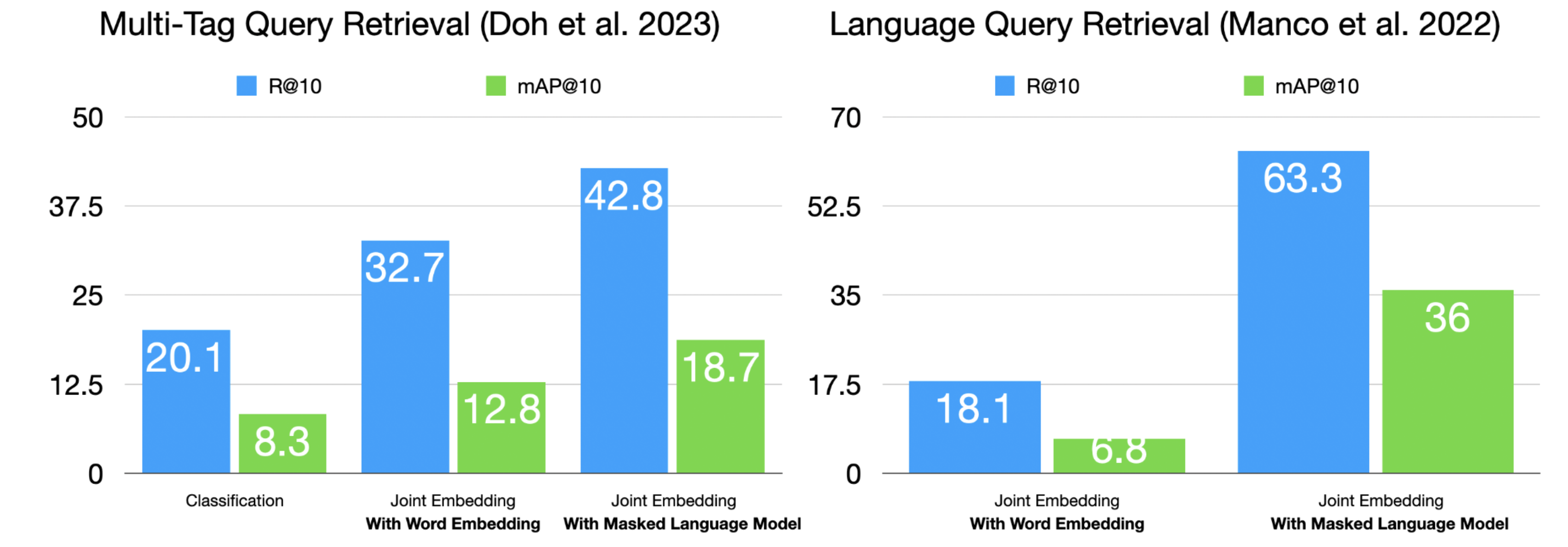

In practice, pre-trained language model text encoders have not shown significant performance improvements in multi-tag query retrieval [DWCN23] and language query retrieval [MBQF22] scenarios.

Beyond semntica attributes, toward handle similarity queries#

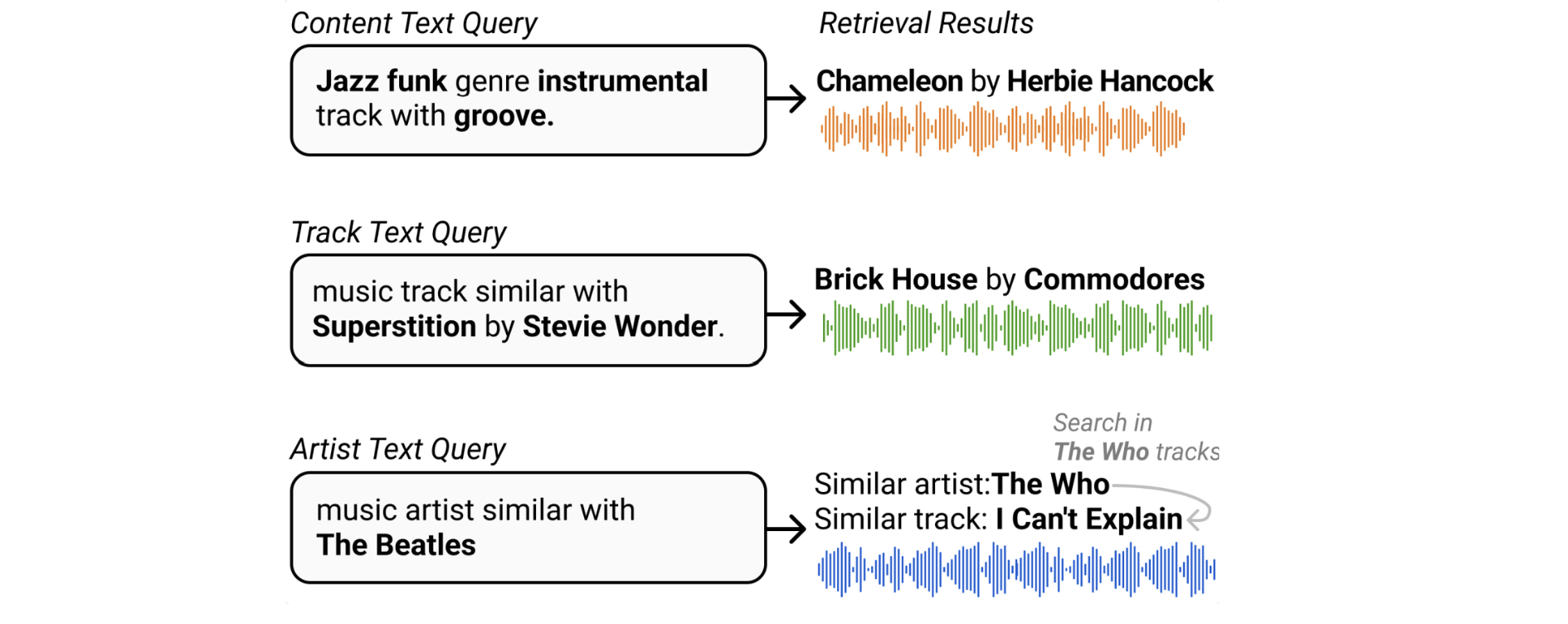

Recent work has explored expanding joint embedding models beyond semantic attribute queries to handle similarity-based search scenarios. While existing datasets and models primarily focus on semantic attributes like genre, mood, instruments, style, and themes, [DLJN24] proposed a novel approach that enables similarity-based queries by leveraging rich metadata and music knowledge graphs.

Specifically, they constructed a large-scale music knowledge graph that captures various relationships between songs, such as artist similarity (songs by artists with similar styles), metadata connections (songs by the same artist), and track-attribute relationships. By training joint embedding models on this knowledge graph, the model learns to understand complex relationships between songs and other musical entities. This allows the system to handle queries like “songs similar to Hotel California” or “music that sounds like early Beatles” by embedding both the query and music in a shared semantic space that captures these rich relationships. The approach significantly expands the capabilities of music retrieval systems, enabling more natural and flexible search experiences that better match how humans think about and relate different pieces of music.

Tips for Training Audio-Text Joint Embedding Models#

Recent research has identified several key strategies for effectively training audio-text joint embedding models that have significantly improved model performance and robustness. One major challenge is query format diversity - models must understand and process queries ranging from simple tags (e.g., “rock”, “energetic”) to complex natural language descriptions (e.g., “a melancholic piano piece with subtle jazz influences”). Additionally, models must bridge the semantic gap between audio features and semantic concepts expressed in text descriptions. Researchers have developed several effective strategies to address these fundamental challenges, which are detailed below.

Leverage Diverse Training Data Sources#

Utilize noisy web-scale text data [HJL+22, WKGS24] to expose models to real-world music descriptions

Combine multiple annotation datasets [DWCN23, MSN24, WCZ+23] to capture various aspects of music-text relationships

This multi-source approach helps models develop robust representations across different description styles and musical concepts

Initialize with Pre-trained Models#

Apply Text Augmentation Techniques#

Employ Strategic Negative Sampling#

Implement hard negative sampling strategies [MSN24, WON+21] to improve discrimination ability

Carefully select challenging negative examples that are semantically similar but distinct

This approach helps models develop the ability to make fine-grained distinctions between similar musical concepts

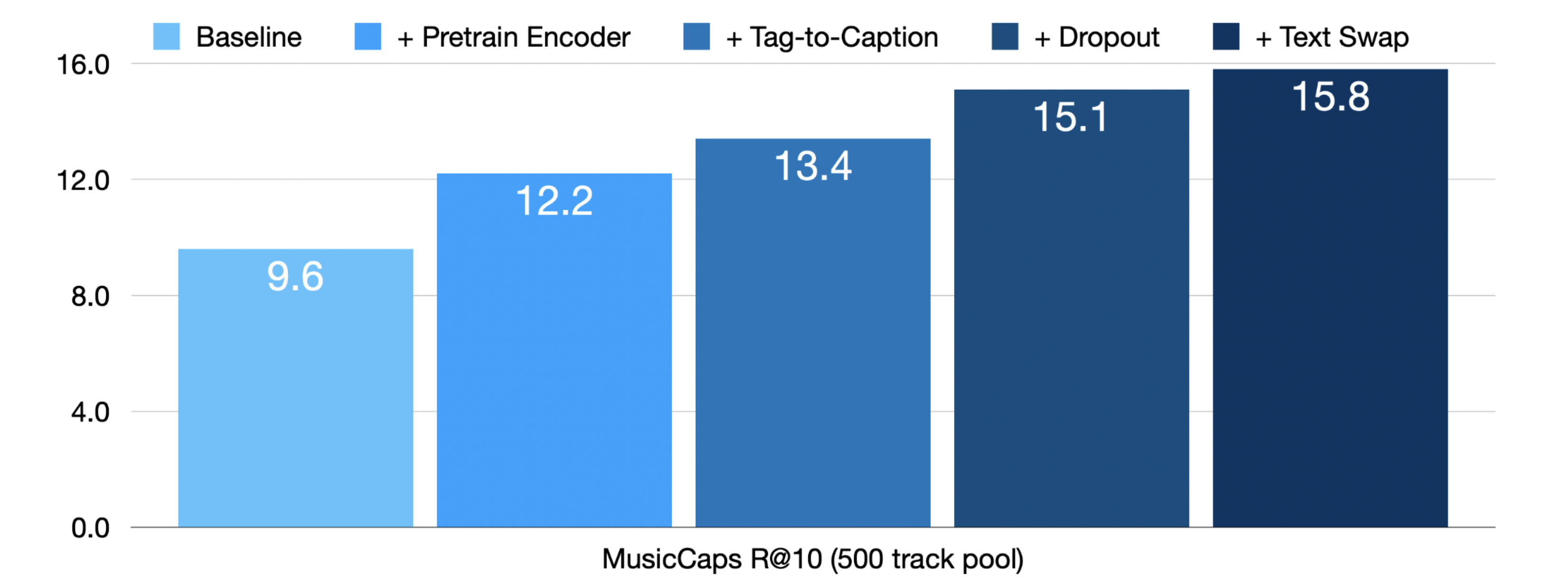

In [MSN24], these ideas were implemented to significantly improve the retrieval performance of audio-text joint embedding models. The experimental results showed dramatic improvements, with the R@10 metric increasing from 9.6 to 15.8 when applying pre-trained encoders, tag-to-caption augmentation, dropout, and hard negative sampling (text swap) techniques on top of the baseline model [DWCN23]. This substantial performance gain demonstrates the effectiveness of combining these training strategies.

References#

Tianyu Chen, Yuan Xie, Shuai Zhang, Shaohan Huang, Haoyi Zhou, and Jianxin Li. Learning music sequence representation from text supervision. In ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 4583–4587. IEEE, 2022.

Jeong Choi, Jongpil Lee, Jiyoung Park, and Juhan Nam. Zero-shot learning for audio-based music classification and tagging. In ISMIR. 2019.

Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. Bert: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805, 2018.

SeungHeon Doh, Jongpil Lee, Dasaem Jeong, and Juhan Nam. Musical word embedding for music tagging and retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.13569, 2024.

SeungHeon Doh, Minz Won, Keunwoo Choi, and Juhan Nam. Toward universal text-to-music retrieval. In ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 1–5. IEEE, 2023.

Qingqing Huang, Aren Jansen, Joonseok Lee, Ravi Ganti, Judith Yue Li, and Daniel PW Ellis. Mulan: a joint embedding of music audio and natural language. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.12415, 2022.

Yinhan Liu. Roberta: a robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692, 2019.

Ilaria Manco, Emmanouil Benetos, Elio Quinton, and György Fazekas. Contrastive audio-language learning for music. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.12208, 2022.

Ilaria Manco, Justin Salamon, and Oriol Nieto. Augment, drop & swap: improving diversity in llm captions for efficient music-text representation learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.11498, 2024.

Aaron van den Oord, Yazhe Li, and Oriol Vinyals. Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding. arXiv:1807.03748, 2018.

Alec Radford, Jong Wook Kim, Chris Hallacy, Aditya Ramesh, Gabriel Goh, Sandhini Agarwal, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Pamela Mishkin, Jack Clark, and others. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International conference on machine learning, 8748–8763. PMLR, 2021.

Benno Weck, Holger Kirchhoff, Peter Grosche, and Xavier Serra. Wikimute: a web-sourced dataset of semantic descriptions for music audio. In International Conference on Multimedia Modeling, 42–56. Springer, 2024.

Minz Won, Sergio Oramas, Oriol Nieto, Fabien Gouyon, and Xavier Serra. Multimodal metric learning for tag-based music retrieval. In ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 591–595. IEEE, 2021.

Yusong Wu, Ke Chen, Tianyu Zhang, Yuchen Hui, Taylor Berg-Kirkpatrick, and Shlomo Dubnov. Large-scale contrastive language-audio pretraining with feature fusion and keyword-to-caption augmentation. In IEEE International Conference on Audio, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). 2023.