The Framework#

In the previous section, we defined language models in the most general sense. In practice, there are a lot more details to know in order to implement and use language models. In this section, we cover the basics and standard practices of dealing with language models, focusing on modern language models using neural networks.

Representation: Text as Sequence of Tokens#

First, to define a probability distribution over some text, we need a way to represent the text which we need to calculate the probability of. The most straightforward way is to treat them as a sequence of words:

Since there are supposed to be a finite number of words in a language, we can assign a class label to each word, so that a categorical probability distribution is defined over all possible words in each location.

In practice, however, the vocabulary size is not really fixed, so we historically resorted to using a special Unknown token for rare or unseen words in the corpus, and a more recent standard practice is to use subword tokenization, which maps uncommon words into multiple subword components, using techniques such as Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) or SentencePiece. In this scheme, complex words like unforgettable, could be decomposed into three tokens, un, forget, and table, for example.

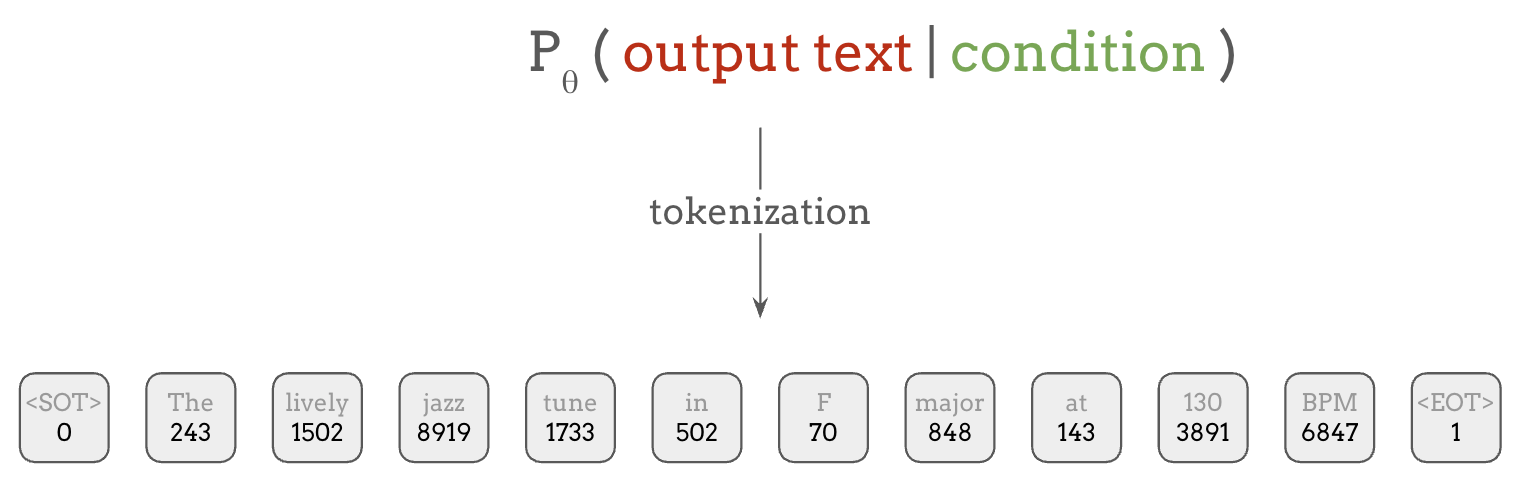

This process is called tokenization, which can encode arbitrary texts into sequence of integers or tokens. These tokens are what language models are trained to predict using categorical distributions.

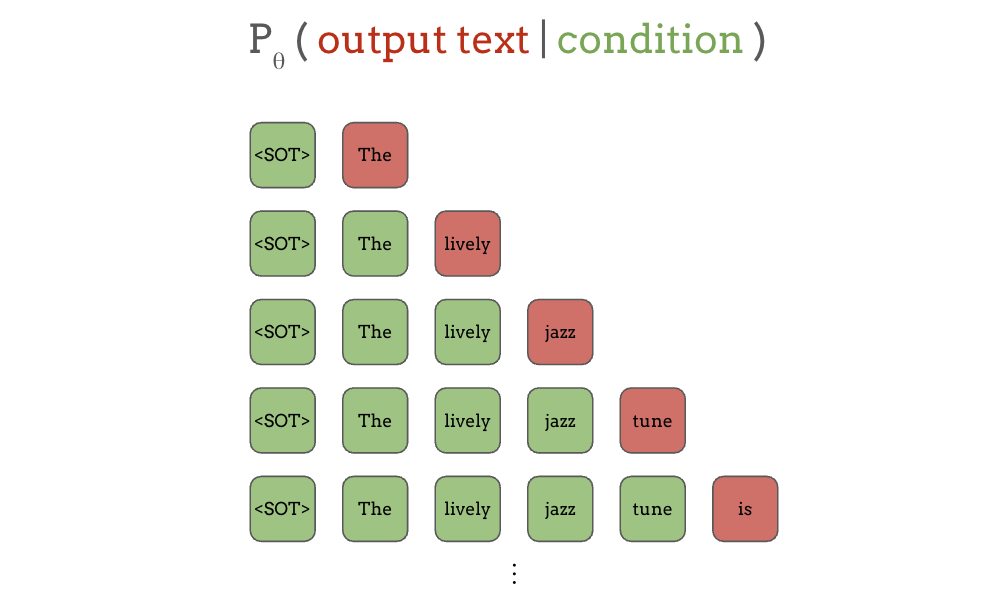

Additionally, for language modeling, it’s common to employ special tokens that are not mapped to words or subwords but have special purposes like marking the beginning and the end of a sentence, like <SOT> and <EOT> in the figure above.

Implementing Language Models#

Since we now covered how texts are represented as sequence of tokens, let’s see how exactly language models can predict those tokens. There can be multiple ways of doing this, but there are two types of approaches that are most widely used.

Masked Language Models#

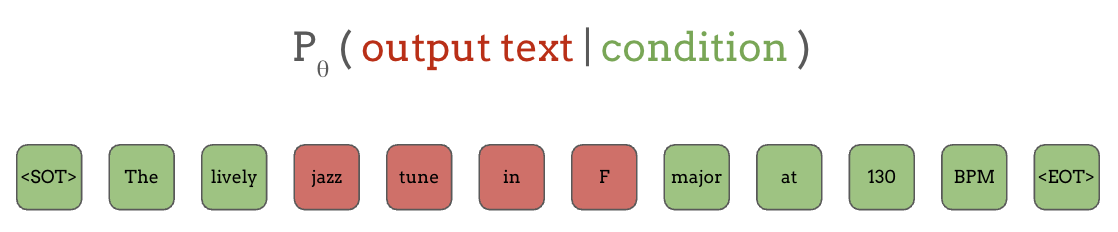

The first is Masked Language Modeling (MLM). In a masked language model, the output text is a sub-sequence of tokens as in the red squares below, and the conditions are the surrounding tokens of that segment as in the green ones. So the model learns to fill in the blank given the contextual information in the sentence, like in English exams.

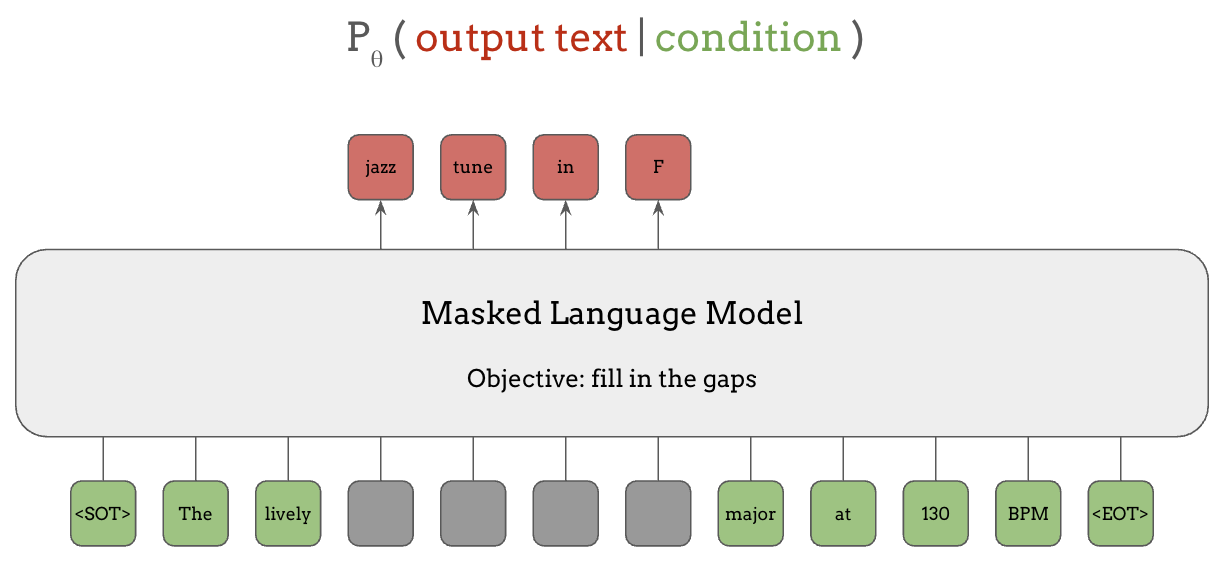

Specifically, in masked language models like BERT, the inputs are the sequence of tokens representing the sentence, shown below in the bottom row with masks applied on the segment of tokens that the model is predicting, as the gray squares, and the output of the model is all of the tokens in the masked segment, shown in red in the top row.

A BERT model trained this way can be used not only for filling in the blanks, but also for transferring the knowledge to solve many other tasks, as we’ll see in the next section.

BERT and similar models like RoBERTa have been tremendously successful at the time when they were released, but more recently, the next kind of language models have become vastly more influential.

Autoregressive Language Models#

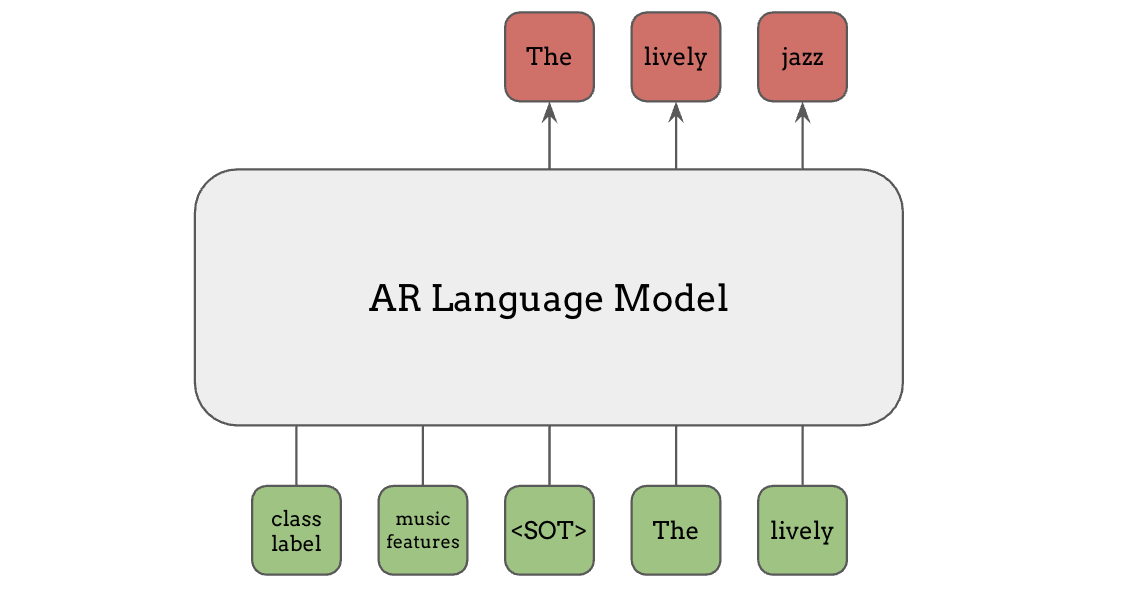

That other major kind of language models is autoregressive, or AR language models, where the model predicts the next token, given all the previous tokens. Again, the green ones are the conditions and the red ones are the outputs in this figure:

First, when only “start of text” is given, the model needs to predict the next word, “The”, and when the start of text and the first word “the” are given, the model predicts the next word, “lively”, and so on.

Although predicting the next token may appear to be a very naïve task, only able to be conditioned on the past and not the future tokens like masked language models did, this simple approach turned out to be extremely effective at learning a variety of tasks from a huge corpus of unlabeled data. It’s partly due to the massive parallelization possible for training this next-word prediction task.

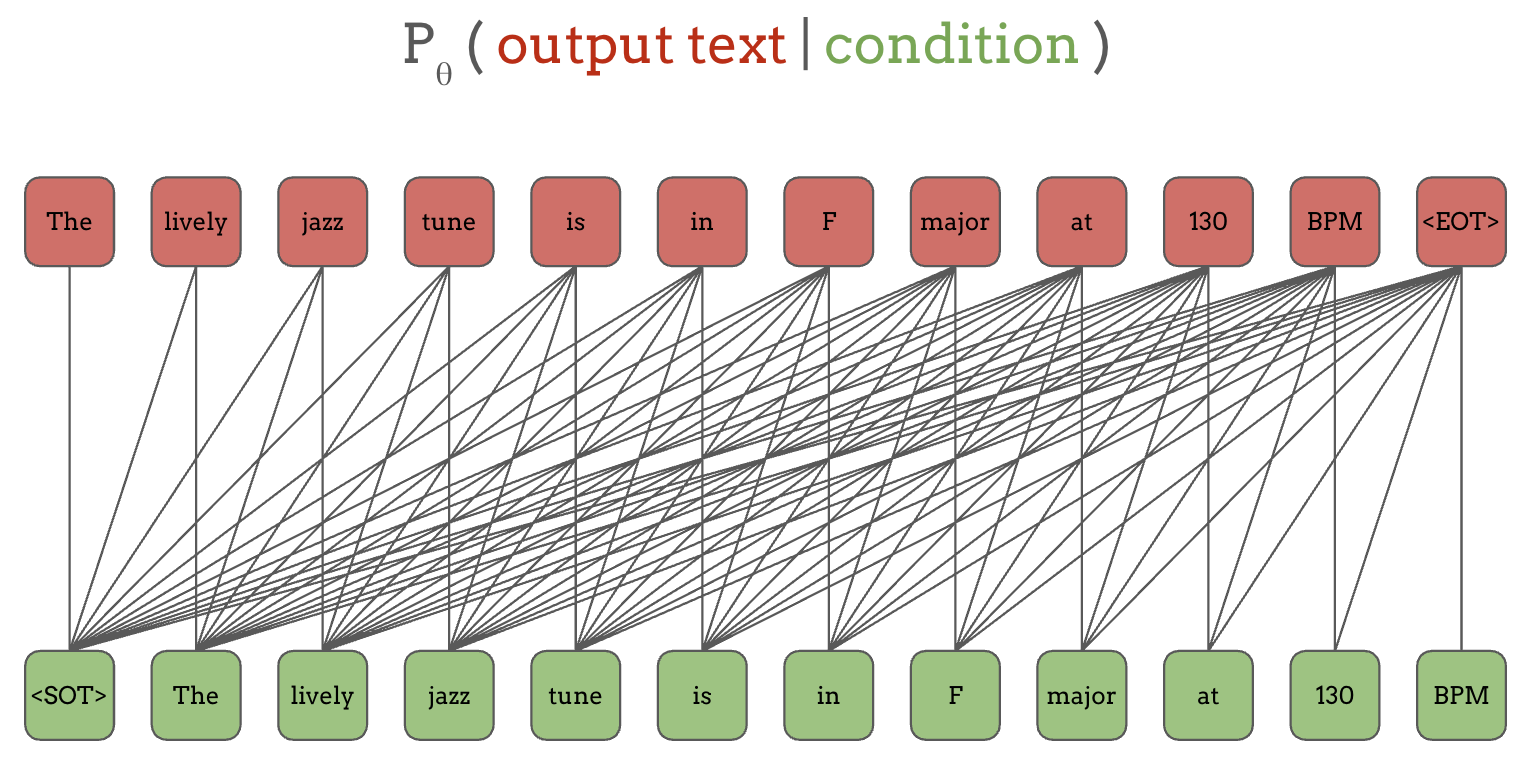

Let’s rearrange the green inputs and the red outputs slightly:

The lines connecting red and green tokens indicate a conditioning relationship. For example, the first output token “The” is conditioned on the first input token “<SOT>”, the second output token “lively” is conditioned on the first two green tokens that it is connected with, “<SOT>” and “The”, and so on. Note that the input tokens in the bottom row and the output tokens in the top row are the same, except shifted by one position.

While these lines look overly complex, autoregressive architectures like RNNs or Transformers with causal masks can enforce that the prediction of certain output token can only depend on the current and past positions. So by training on the input and the same output, just shifted by one position, it effectively does multi-task training on all of the output tokens and their corresponding contexts.

Compared to this, the previous BERT example was predicting only a small subset of the tokens at each time, limiting how much it can learn (i.e. how many tasks it is being supervised for) despite being able to see the future tokens.

Conditioning#

In the above, we covered the “output text” part of the implementation of language models. What about conditioning?

When the conditions are in text, they can be represented as sequence of tokens in the same way as the output text. But they don’t have to be text or make up any probability distribution! They can be continuous features like Mel spectrograms or learned features. Basically, we can be a lot more flexible in how the conditioning information is fed to the language model.

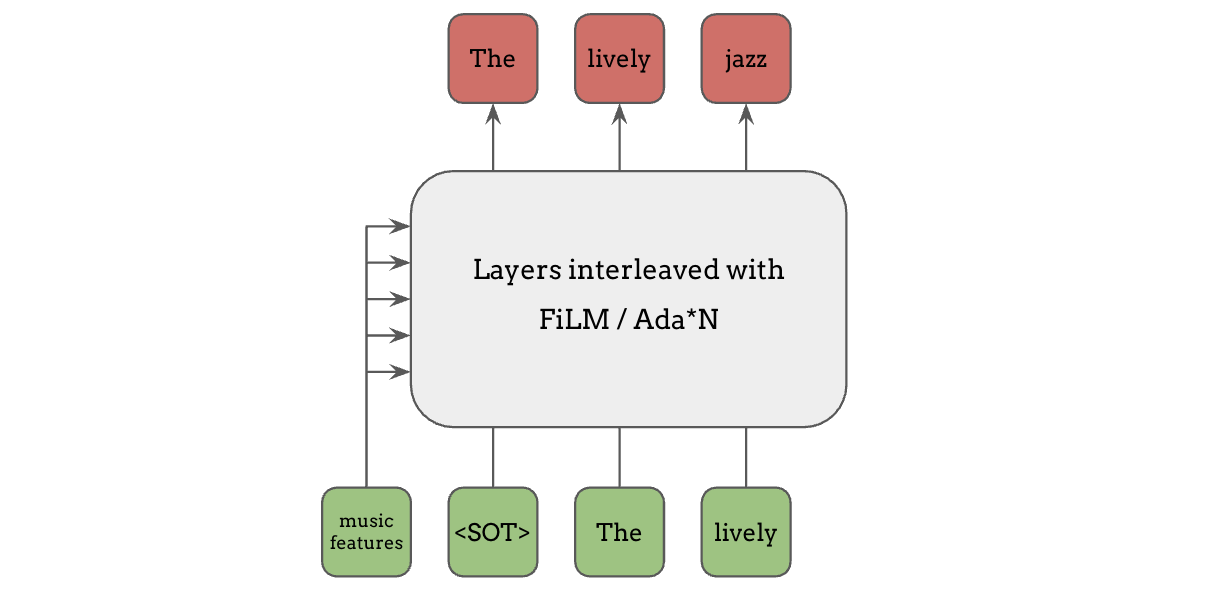

Adaptive Modulation/Normalization#

Say we want to condition a language model on some features, one common way is to adapt a hidden layer or a normalization layer in the network based on the conditional inputs, such as FiLM, Adaptive Instance Normalization, Adaptive Layer Normalization etc. These are very effective because conditioning information can affect every layer of computation inside a network.

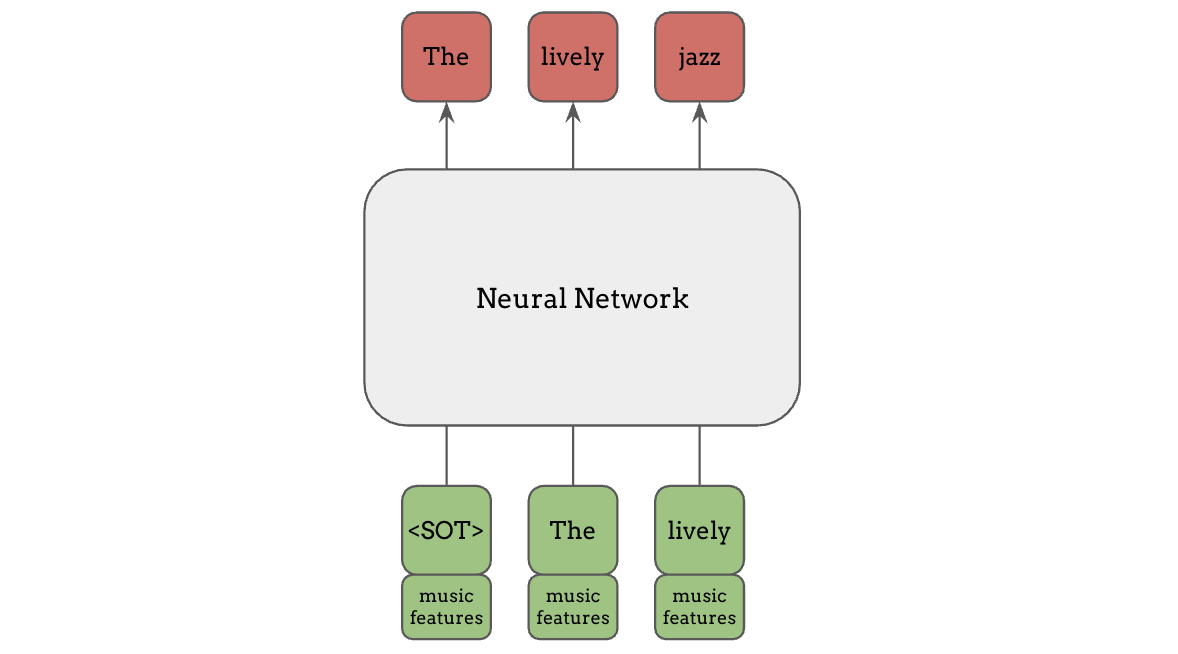

Channel Concatenation#

An alternative way is to concatenate the conditioning information in the channel domain of the input, which is a simpler and computationally cheaper method which still can work pretty effectively. This is especially useful when we already know that the input tokens are aligned with the features, in which case we can supply specific matching features for each token, instead of broadcasting the same features for all tokens.

The two methods above for conditioning are not specific for language models and are applied for other kinds of neural networks, such as conditional GANs.

Prefix Conditioning#

In the context of language models and Transformers, prefix conditioning is another common method for conditioning language models. The conditioning information such as class labels or music features can be fed to the language model as additional tokens preceding the main put, as shown in green here. Unlike the text tokens, this information does not have to be in discrete integers, and any continuous features can be used here, just projected onto the same dimension as the token embeddings.

Encoder-Decoder Attention (a.k.a. Cross Attention)#

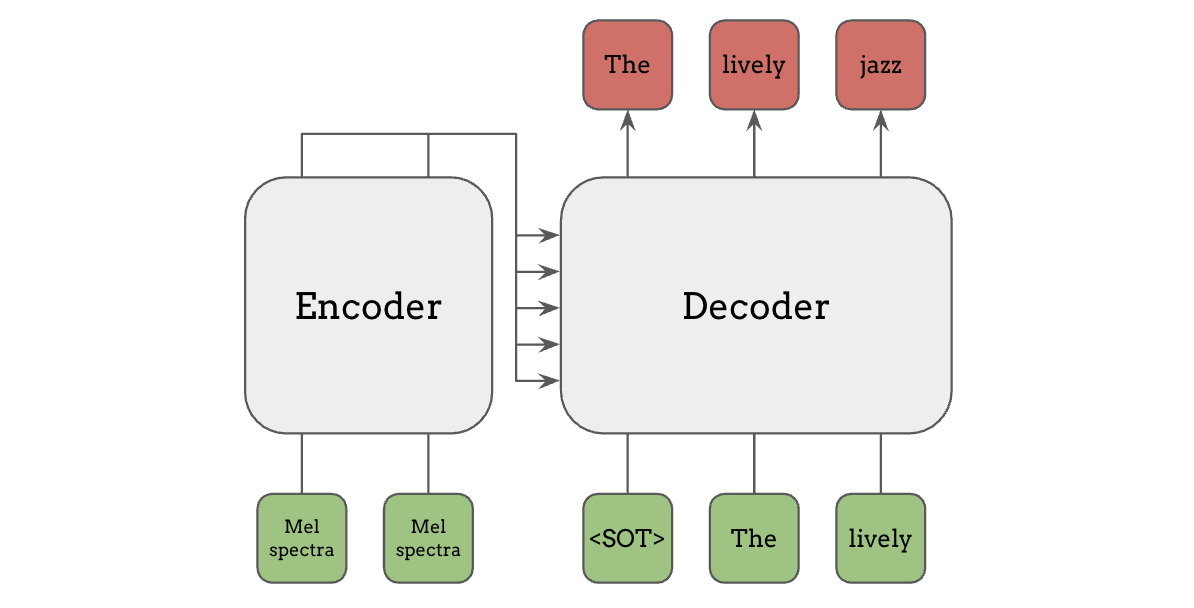

Lastly, encoder-decoder attention, or cross attention is a more flexible method for conditioning, where a separate encoder model is used for computing the features of the conditioning inputs, such as Mel spectrogram, and those features are used in the attention mechanism in the decoder. This encoder-decoder architecture is what was used in the original Transformer paper “Attention is All You Need”, and also in the models like T5 and Whisper.

Language Models as a Framework#

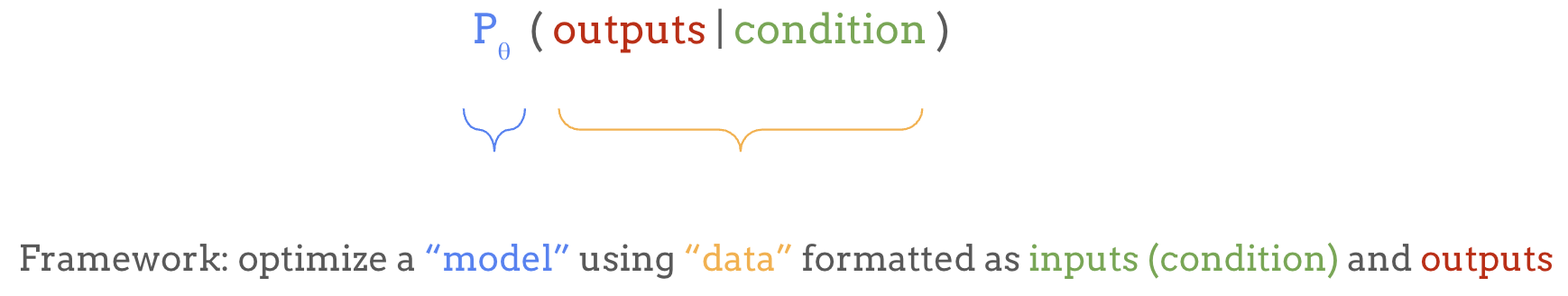

In this section, we have covered what language models are and how the conditioning inputs and the output tokens are connected. The inputs can be basically anything, and as long as we can represent the output as a sequence of discrete tokens, language models can provide a simple, general-purpose framework for almost any machine learning problem:

The majority of research advances introduced in this tutorial are adaptations or extensions of this framework. In the following section, starting from some limitations of this framework, we introduce a variety of applications and extensions of language models.