Background#

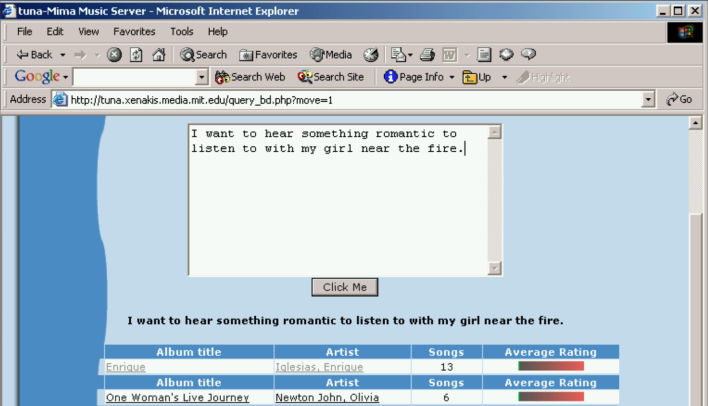

Fig. 2 Image Source: Learning the Meaning of Music by Brian A. Whitman, 2005, Massachusetts Institute of Technology(MIT)#

The journey of Music and Language Models started with two basic human desires: to understand music deeply and to listen to the music we want whenever we want, whether it’s existing artist music or creative new music. These fundamental needs have driven the development of technologies that connect music and language. This is because language is the most fundamental communication channel we use, and through this language, we aim to communicate with machines.

Early Stage of Music Annotation and Retrieval#

The first approach was Supervised Classification. This method involved developing models that could predict appropriate Natural Language Labels (Fixed-Vocabulary) for given audio inputs. These labels could cover a wide range of musical attributes including genre, mood, style, instruments, usage, theme, key, tempo, and more [SLC07]. The advantage of Supervised Classification was that it automated the annotation process. As music databases grew richer with these annotations, in the retrieval phase, cascading filters could be used to find desired music more easily. Alternatively, the output logits from supervised learning could be used to find the music tracks closest to a given word [ELBMG07] [Lam08] [TBTL08]. The research on supervised classification evolved over time. In the early 2000s, with advancements in pattern recognition methodologies, the focus was primarily on feature engineering [FLTZ10]. As we entered the 2010s, with the rise of deep learning, the emphasis shifted towards model engineering [NCL+18].

However, supervised classification has two fundamental limitations. First, it only supports music understanding and search using fixed labels. This creates a problem where the model cannot handle unseen vocabulary. Second, language labels are represented through one-hot encoding, which means the model cannot capture relationships between different language labels. As a result, the trained model is specifically learned for the given supervision, limiting its ability to generalize and understand a wide range of musical language.

Note

If you’re particularly interested in this area, please refer to the following tutorial:

Early Stage of Music Generation#

Compared to Discriminative Models \(p(y|x)\), which are relatively easier to model, Generative Models \(p(x|c)\) that need to model data distributions initially focused on generating short single-instrument pieces or speech datasets rather than complex multi-track music. In the early stages, unconditioned generation \(p(x)\) methods such as likelihood-based models (represented by WaveNet [VDODZ+16] and SampleRNN [MKG+16]) or adversarial models (represented by WaveGAN [DMP19]) were studied.

Early Conditioned Generation models \(p(x|c)\) included the Universal Music Translation Network [MWPT19], which used a single shared encoder and different decoders for each instrument condition, and NSynth [ERR+17], which added pitch conditioning to WaveNet Autoencoders. These models represented some of the first attempts at controlled music generation.

However, Generative Models capable of Natural Language Conditioning were not yet available at this stage. Despite the challenge of generating high-quality audio with long-term consistency, these early models laid the groundwork for future advancements in music generation technology.

Note

If you’re particularly interested in this area, please refer to the following tutorial:

References#

Chris Donahue, Julian McAuley, and Miller Puckette. Adversarial audio synthesis. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). 2019.

Douglas Eck, Paul Lamere, Thierry Bertin-Mahieux, and Stephen Green. Automatic generation of social tags for music recommendation. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2007.

Jesse Engel, Cinjon Resnick, Adam Roberts, Sander Dieleman, Mohammad Norouzi, Douglas Eck, and Karen Simonyan. Neural audio synthesis of musical notes with wavenet autoencoders. In International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2017.

Zhouyu Fu, Guojun Lu, Kai Ming Ting, and Dengsheng Zhang. A survey of audio-based music classification and annotation. IEEE transactions on multimedia, 2010.

Paul Lamere. Social tagging and music information retrieval. Journal of new music research, 2008.

Soroush Mehri, Kundan Kumar, Ishaan Gulrajani, Rithesh Kumar, Shubham Jain, Jose Sotelo, Aaron Courville, and Yoshua Bengio. Samplernn: an unconditional end-to-end neural audio generation model. arXiv preprint arXiv:1612.07837, 2016.

Noam Mor, Lior Wolf, Adam Polyak, and Yaniv Taigman. A universal music translation network. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). 2019.

Juhan Nam, Keunwoo Choi, Jongpil Lee, Szu-Yu Chou, and Yi-Hsuan Yang. Deep learning for audio-based music classification and tagging: teaching computers to distinguish rock from bach. IEEE signal processing magazine, 2018.

Mohamed Sordo, Cyril Laurier, and Oscar Celma. Annotating music collections: how content-based similarity helps to propagate labels. In ISMIR, 531–534. 2007.

Douglas Turnbull, Luke Barrington, David Torres, and Gert Lanckriet. Semantic annotation and retrieval of music and sound effects. IEEE Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, 16(2):467–476, 2008.

Aaron Van Den Oord, Sander Dieleman, Heiga Zen, Karen Simonyan, Oriol Vinyals, Alex Graves, Nal Kalchbrenner, Andrew Senior, Koray Kavukcuoglu, and others. Wavenet: a generative model for raw audio. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.03499, 2016.